What It’s Really Like to Be Young, Black, and an African Tech Startup Entrepreneur (in Africa)

Cross-posted from Wiza’s blog on Medium.

This post is going to read like a vaguely-connected set of thoughts and ideas. I have a habit of writing running sentences and occasionally going off-topic to introduce a new rant, mid the current rant that I’m ranting.

I’ve been thinking about this post for a while but haven’t been feeling quite confident about writing it, so a special thanks to Nigel, Hungai, Mbwana, Sam, Juanita, Swigi, Sam (again), Ndauka, Friday, Wusigala, my Dad, Michael, Aku and so many others for giving me the courage to do this.

Right then, back to the main topic. Being a startup founder anywhere in the world is incredibly hard, but in Africa, it’s a special kind of organised chaos.

It’s not pretty.

I’m nearly 24 years old, and over the last 8 years, I’ve built and launched 3 technology companies in Africa across different verticals in two countries. The first one when I was 16 years old — I didn’t even know that it was a startup at the time, and it failed.

A few years later, I built a web technology startup, got very limited traction that reached a plateau, so I converted it to a web hosting company for passive income.

In 2014, I co-founded a market research startup.

We raised $30,000 in venture capital from a Pan-African VC firm (Savannah Fund), went through an incredible accelerator experience, executed as best we could, but still faced incredible challenges.

I had thought that with such significant experience, maybe we’d be able to pull it off, but time and again, I got my ass handed to me by the business environment. It is relentless and unforgiving.

A few months ago I was down to my last 100 dollars, getting ready to sell everything in my apartment in Nairobi to raise airfare to fly back to my parents’ home in Lilongwe and call it a day.

It was over. I had tried and failed, and I had no more energy to keep trying. I’d spent the last 17 months working almost every single day to build Djuaji Research Limited — a platform to facilitate scalable survey-based research to help businesses obtain data at low cost by paying respondents with mobile money. It was a genius concept developed by my co-founder and classmate at the time, Hungai. I joined when it was just a concept while we were both studying at United States International University (in Kenya, despite the name), and we agreed to start the business together.

I turned down several decent opportunities with reputable local and international technology companies (including Google and Oracle) to do this, so it wasn’t easy but it was worth it.

Djuaji Team at Pivot East 2015 (Finalists baybay haha!)

We built some incredible tech and actually made a lot of progress, but even then, it wasn’t enough. We were months away from a feasible MVP and burning cash way too fast with very few alternatives. Raising another round was not possible, we had traction but not enough to convince investors to inject more cash. We had a lot of interest from a global traditional research firm and we were working on a specific project with them that would open up a lot of doors, and potentially cash, if we managed to pull it off.

The problem was, however, that we just didn’t have enough time. We needed more time to build the product, deploy it in a pilot with the research firm and prove that the idea could work. But there was no time. To get time, we needed money, and we couldn’t get that either.

<rant>For as long as you aren’t yet profitable, time is the only resource you have as a startup. Every other apparent resource is just a factor of how you spend that time.</rant>

I thought deeply about the problem for weeks, and had a series of conversations with my co-founder. I ran the numbers, tried to cut costs and project for the future but time and time again, I found myself staring at an Excel sheet stating the painfully obvious to me — that there was no way of doing this without drastically cutting costs or finding a new revenue source.

Then it hit me. By virtue of being a foreigner in Kenya (I’m Malawian), I was the most expensive member of the team. Stipends and costs related to me were significantly higher than my co-founders’ and our team members.

When I ran the numbers again and removed all costs related to me, the company had enough time to attempt this project and hopefully survive.

I had a talk about it with my co-founder and we agreed that it would buy us time, but losing a co-founder would also put the company at significant risk.

I was the one who handled all of the business development at Djuaji, while my co-founder was responsible for designing and building the tech. We had reached a point where there was a viable business model that needed to be tested but we could not come to an agreement on what the best way forward was. I think that ultimately, we had different visions for what we wanted the company to evolve into and I believed that at that point, we could only execute one vision.

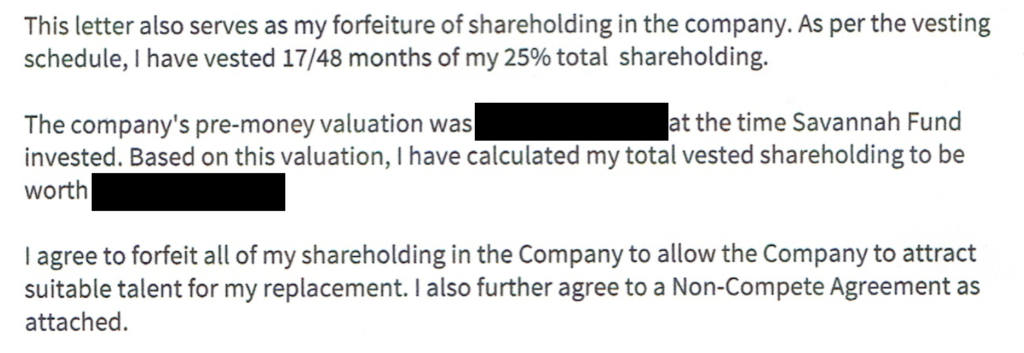

After a few more days of thought and discussion, I made the decision to resign from my position as co-founder and COO of Djuaji Research Limited.

It’s very easy to look at that decision and brand me a coward for it. It’s easy to think that I gave up too soon and let my team and my investors down by leaving.

The day I wrote my resignation letter was one of the most painful of my whole life, and I remember tearing up as I watched it printing.

It was the first time I had shed tears in such a long time.

Despite what you may expect from a decision like that, I honestly believe that my resignation saved the company from bankruptcy. I didn’t just pack up and leave. I did everything I could to make my departure as painless as possible and to put the Company in the best possible position to survive.

I made a lot of painful sacrifices and voluntarily gave up all of my hard earned equity, unconditionally.

Telling my team I was leaving was as difficult as you can imagine, but the really tough conversation that remained was with my investor.

I thought long and hard about what to say to Mbwana, the managing partner of Savannah Fund who had spent a lot of his own time and effort into helping us build the company.

I felt like anything I would say to him would sound like “Hey dude, thanks for the cash, it’s been real but this isn’t working for me anymore, so peace!”when the reality was far much complex.

I guess, when someone has invested money in you, there’s a slight temptation to always want to report the good news and downplay the bad so it doesn’t seem like you’re a clueless idiot recklessly playing around with money.

I didn’t get everything right during my time at Djuaji but one thing that I did get right that I’m very proud of is maintaining honest investor relations. We always were forthcoming with investors especially when we failed at something and that actually saved us a lot of time and worry. One of the hardest things for me was learning to accept failure as part of the process in a startup.

<rant>I think this is potentially a side-effect of African culture, you spend your whole life being punished and reprimanded when you fail and all of a sudden someone is telling you that failure is good. What do you mean?</rant>

I mustered up all the courage I had and scheduled a Skype call with Mbwana. When I first told him about my intention to leave, I expected him to be upset about it, but instead, we had a long and fruitful conversation about the nuances of running an African startup.

I’m happy to say that despite all of the above, I still maintain a very amicable relationship with both my co-founder and my investor as we all work collaboratively to improve the ecosystem as a whole.

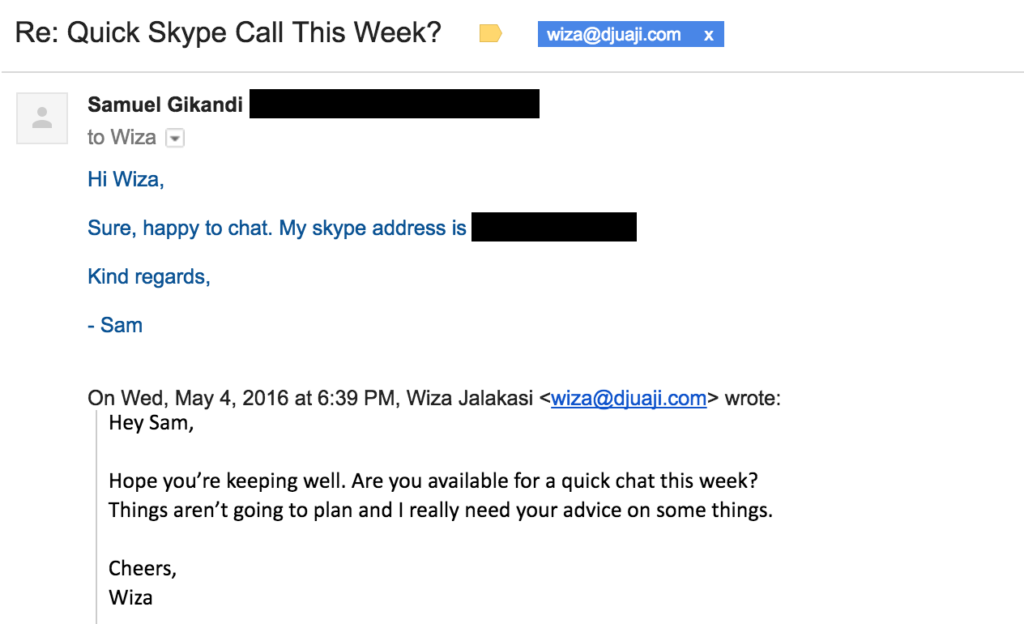

It was really, really difficult to have that conversation with my investor. Before I did, I sent an email to 5 people who I thought would be able to shed a little light on what to do with my situation. I only got one response.

Sam Gikandi is the co-founder and CEO of Africa’s Talking, where I recently joined as a business development lead. My original plan was to clean up shop after leaving Djuaji, and then go back to my home in Malawi and develop bulk SMS applications on top of their APIs to raise money to try a few ideas I have with drones.

<rant>Aviation is my first love. Technology comes second. When I have enough money and experience, I’m going to learn how to fly so I can build aviation safety technology, and I will probably spend the rest of my life doing that. Till then, I’ve been teaching myself with consumer simulators. I have over 9,000 hours and can comfortably fly a manufacturer-certified simulation of the Boeing 737. Procedurally and correctly, from cold and dark to landing, even under instrument meteorological conditions. If you think I’m lying, ask me a question.

</rant>

At the end of that Skype call was a job offer.

I was really conflicted about it at first because I’d never been employed before and the thought of sitting down at a desk flipping through Office app screens all day makes me sick.

A few conversations later and a two week break later, I chose in.

After I had a chance to learn more about the company and the culture, I’m very happy I joined. It’s still very much a startup that’s at the scaling stage and it’s been one hell of a journey.

Faizal Okhai (Access Malawi CEO), Me and Chrispin Kampangire (Access Malawi Core Network Manager)

In the few months I’ve been working with AT, I’ve established a Malawi office, pitched and won 4 telecoms companies, hired arguably the best person in the country to help me build the local office and travelled between 3 countries to try and get people to understand the vision and why we make the technology that we make.

Me + Africa’s Talking DemoPod at the GSMA Mobile 360 Africa Conference 2016 — Dar es Salaam, TZ

I really love working at AT because I’ve been on the other side of the table. My first startup, MwTunes.com (2009), failed to take off or monetise because I couldn’t convince the Malawian telephone companies to give me access to their infrastructure for billing or ads. In their defence, I was barely 18 with bad hair and baggy trousers so maybe I didn’t inspire the most confidence.

If AT existed at the time, I’d have spent 15 minutes integrating their API with MwTunes and the job would be done. I don’t even like to think about it these days, because the pain is frustrating.

Whatever the case, I’ve started seeing the incredible power of APIs in Africa and I’m really excited to see what the future of African tech will develop into because of them.

Building technology for Africa is hard, and no I’m not just whining about it. I’ve spent most of my life doing it, and I think I’m fairly well qualified for it to.

One of the biggest problems I see at present is the lack of true African stories. Everything you read online about startup success is typically about a white male who dropped out of an Ivy League school, raised a ton of money and built a company with it. Where are the African stories? That’s why I’m writing this blog.

Secondly, the global media has such a pessimistic narrative of Africa as a continent. I was so surprised when I woke up last month in my hotel room in Dar es Salaam and this was my view.

Fun challenge: spot the poverty in this picture

I think the world is really changing and Africa really is rising, despite what the media says. The solutions for Africa, solving African problems will come out of Africa and be championed by Africans. This is the future I see.

Over the next few months, I hope to write more about my experiences and learn from anyone who wants to share. Please share this post if you found it worthwhile and follow me on Medium for more of these posts. I’m also looking for people to help read and edit these before they go live, so if you’re interested and actually have experience writing, please get in touch.